How GPS and Impeller Systems Measure Stroke Rate

Want to measure your rowing stroke rate accurately? Two main technologies can help: impeller systems and GPS systems. Here’s a quick breakdown:

- Impeller systems: Measure speed relative to the water by tracking impeller rotations. They’re highly accurate (within 2%) and ideal for moving water with currents.

- GPS systems: Use satellites to calculate speed over ground. They’re easy to set up and work best on still water but can be less precise (errors over 10% for single strokes).

Both systems have strengths and weaknesses. Impellers excel in precision and real-time feedback, while GPS offers simplicity and broader performance tracking. Many modern devices combine both for the best of both worlds.

Key takeaway: Choose impellers for technical drills and moving water, GPS for still water and distance tracking, or a hybrid device for maximum flexibility.

How Impeller Systems Work

How Impellers Measure Water Flow

Impeller systems function on a simple yet effective principle: the movement of water drives a hull-mounted impeller, spinning it at a speed that matches the boat’s motion. As the water flows, the impeller rotates, and a wireless sensor inside the boat tracks this rotation without requiring any modifications to the hull. By analyzing the impeller’s rotations, the system calculates key metrics like distance traveled, boat speed, and stroke rate. These measurements depend on precise calibration to ensure accuracy.

"Impeller measurement is based on the principle that the water sets it in a motion that corresponds with the speed of the boat that it is attached to." – Dr. Volker Nolte, Expert on Biomechanics

Calibration and Accuracy Factors

Calibration plays a central role in ensuring accurate readings. To avoid interference from laminar flow near the bow, the sensor should be mounted roughly 16 feet (5 meters) from the front of the boat, placing the impeller in a stable turbulent boundary layer.

When calibrated properly, an impeller system can deliver accuracy within 2% for any measurement. This means a variance of less than 1.5 seconds over 500 meters under typical conditions. The calibration process involves rowing a known distance – usually between 500 and 1,000 meters – in both directions to cancel out environmental factors like wind, tides, or currents. Although factory settings start with a calibration value of 1.000, adjustments are often needed to account for differences in hull design and impeller placement.

Maintaining a clean bow is also critical to avoid disruptions in water flow. The impeller system’s hydrodynamic design adds only about 0.1% to the total drag of a single scull, which is even less than the drag caused by a standard skeg. This level of precision ensures reliable data for analyzing stroke rates and overall performance.

Common Impeller-Based Devices

One of the most popular devices supporting impeller technology is the SpeedCoach GPS Model 2, priced at $469.00 (excluding the impeller and wiring). While it incorporates GPS functionality, it remains impeller-compatible to provide unmatched accuracy in moving water. The device also uses an internal 3-axis accelerometer to wirelessly track stroke rate, while the impeller measures speed and distance.

Other models tailored for specific activities include the SpeedCoach OC 2 for outrigger canoes and the SUP 2 for stand-up paddleboarding, both utilizing impeller systems for water-relative metrics. Older models, such as the SpeedCoach Red, Gold, and XL, also rely on impeller technology.

"Training with an impeller has been the gold standard for rowing for years, especially for teams that train on moving water." – NK Sports

These devices combine advanced technology with reliable measurement capabilities, making them indispensable for training and performance analysis in competitive water sports.

How GPS Systems Work

GPS Measurement Methods

GPS technology relies on satellite signals to determine location and performance metrics. Each satellite broadcasts precise time and location data, and a boat’s GPS device uses a process called trilateration to calculate its 3D position. This involves measuring the travel time of signals from at least four satellites.

"Operation of the Scullr GPS rowing computer is controlled by two buttons, as well as the accelerometer and Global Positioning System (GPS) receiver. The buttons control the user interface, the accelerometer detects strokes through movement of the boat, and the GPS receiver determines the speeds and distance traveled." – Dr. Henry Thomas, Scullr

Speed is calculated by tracking changes in position over time. Modern GPS systems often enhance accuracy by combining data from the GPS receiver with inputs from accelerometers and gyroscopes through a process known as sensor fusion.

Stroke rate measurement, on the other hand, primarily depends on the accelerometer rather than satellite signals. The accelerometer identifies rhythmic acceleration peaks and movement patterns caused by each stroke. Advanced systems even use Rowing Dead Reckoning (RDR) algorithms, which analyze forward acceleration and rotational velocity to detect the end of each stroke. After powering on, the device may take up to 30 seconds to connect to enough satellites (ideally five or more) for a stable location fix.

These methods provide a solid foundation for understanding GPS functionality, though real-world conditions can still impact accuracy.

GPS Accuracy Limitations

Although GPS systems deliver reliable data, several factors can limit their accuracy. Standard GPS typically provides around 7.0-meter precision. While this level of accuracy is fine for tracking total distance and average speed, it struggles to capture the subtle velocity shifts within each stroke cycle. Devices like the u-blox MAX-6 GNSS receiver, used in rowing research, offer improved accuracy, with a horizontal position precision of 2.5 meters and velocity accuracy of 0.1 m/s.

On-water GPS accuracy can be influenced by several factors. For instance, signal delays caused by the ionosphere and troposphere can introduce errors, which the receiver must correct. The satellite constellation’s geometry also matters – a more evenly spaced distribution of satellites enhances precision. In August 2024, researchers Luis Rodriguez Mendoza and Kyle O’Keefe tested a wearable prototype at the Victoria City Rowing Club using a Hudson single scull. Their system, which combined a U-blox ZED-F9P GNSS receiver with an MPU6050 IMU, achieved positioning accuracy between ±0.185 meters and ±1.656 meters while monitoring stroke rates ranging from 18 to 36 strokes per minute.

For even greater precision, technologies like Differential GNSS (DGNSS) and Real-Time Kinematic (RTK) systems can achieve centimeter-level accuracy (±0.01 meters) in open-sky conditions. However, for most rowers, the ±2-meter precision of consumer GPS devices is sufficient for tracking workout metrics like distance, average speed, and stroke rate trends. To ensure accurate readings, rowers should securely mount their GPS units to the rigger or boat. Loose mounting can cause the accelerometer to misinterpret boat movements, especially in rough water, leading to incorrect stroke counts.

GPS vs. Impeller Systems

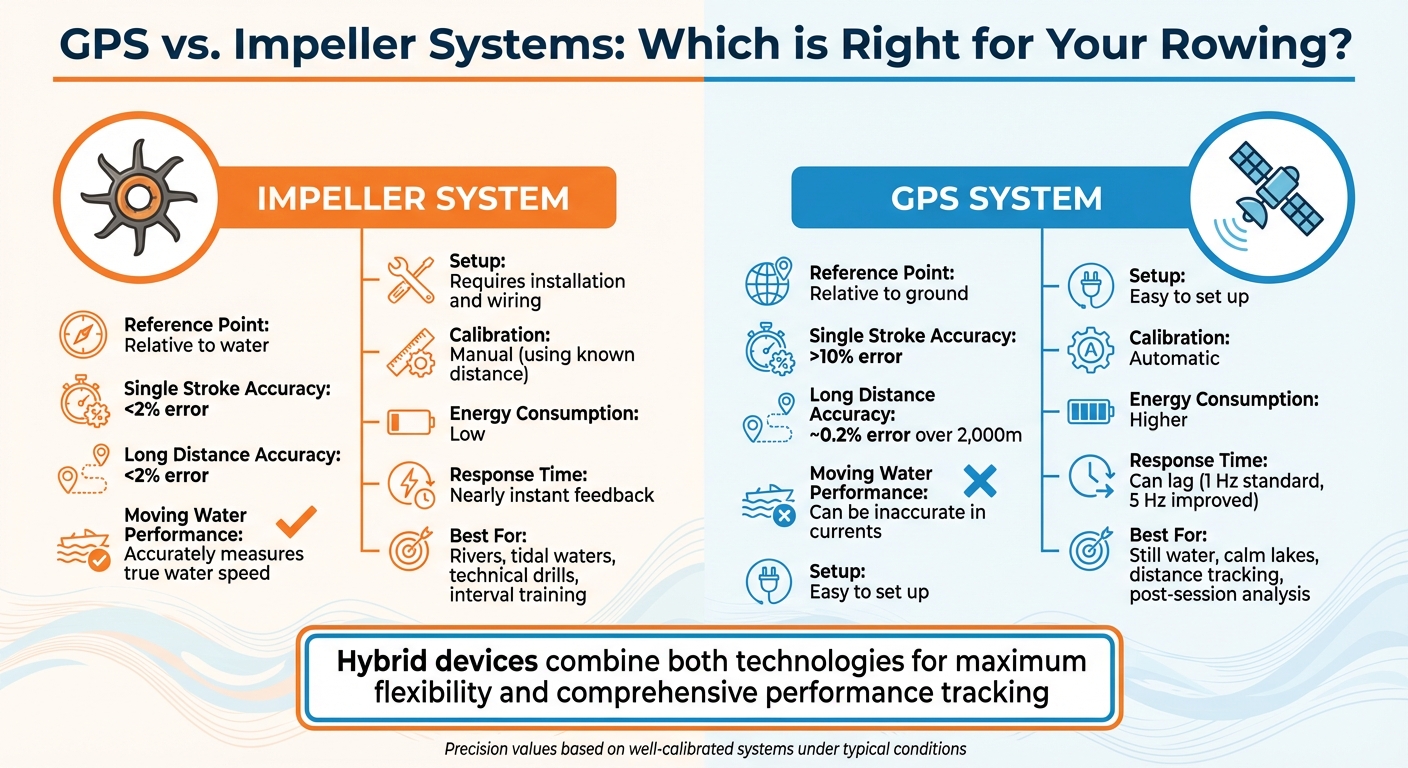

GPS vs Impeller Systems for Rowing: Accuracy and Performance Comparison

Accuracy and Performance Differences

GPS and impeller systems measure rowing performance differently. GPS tracks speed relative to the ground, while impeller systems measure speed relative to the water – a crucial distinction when rowing in currents or moving water. For stroke-by-stroke accuracy, a well-calibrated impeller typically keeps errors below 2%, whereas GPS can have errors exceeding 10% for individual strokes due to positional inaccuracies. Over longer distances, however, high-quality GPS devices can reduce random error to about 0.2%. Here’s a quick comparison:

| Feature | Impeller System | GPS System |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Point | Relative to water | Relative to ground |

| Single Stroke Accuracy | < 2% error | > 10% error |

| Long Distance Accuracy | < 2% error | ~0.2% error over 2,000m |

| Moving Water Performance | Accurately measures true water speed | Can be inaccurate in currents |

| Setup | Requires installation and wiring | Easy to set up |

| Calibration | Manual (using a known distance) | Automatic |

| Energy Consumption | Low | Higher |

Response time also sets these systems apart. Standard GPS devices (1 Hz) can lag, requiring smoothing filters to handle noisy data. Higher-end GPS models with 5 Hz sampling and accelerometers offer quicker, more responsive updates. On the other hand, impellers provide nearly instant feedback for each stroke, making them highly effective for real-time performance tracking.

"The information generated by GPS is potentially extremely inaccurate, especially when used on a body of water with current. Used without consideration of this fact, the training feedback could harm an athlete’s development or even health."

– Dr. Volker Nolte, Expert in Biomechanics

Each system is also impacted by environmental factors. Impellers can be disrupted by algae or debris clogging the sensor, while GPS relies on satellite signals, which can be hindered by cloud cover, atmospheric conditions, or physical obstructions like trees or bridges.

When to Use Each System

Choosing the right system depends on the rowing conditions. Impellers excel in environments with significant water movement, as they measure true water speed and are unaffected by currents. GPS, in contrast, is better suited for still water settings – like calm lakes or bays – where ground speed and distance tracking are the main priorities.

For technical drills and interval training that require precise, stroke-by-stroke feedback, impellers are the go-to choice. Their accuracy and immediate response help fine-tune technique. Many modern rowing devices now allow switching between GPS and impeller modes, combining the convenience of GPS mapping and post-session analysis with the precise, instant data of impellers. This hybrid approach provides a fuller picture of performance, aiding both real-time adjustments and long-term improvement.

Using Stroke Rate Data in Training and Racing

Analyzing Stroke Rate Data

Stroke rate data becomes a powerful tool when aligned with specific training objectives. For instance, technique drills performed at 18–22 strokes per minute (spm) often highlight technical flaws due to the increased load per stroke. On the other hand, steady-state endurance sessions typically operate at 24–28 spm, striking a balance between aerobic conditioning and maintaining proper form. When it comes to race-pace intervals or 2,000m races, stroke rates climb to 30–36 spm, with elite crews sometimes finishing races at an astonishing 47 spm.

The relationship between stroke rate and pace can also reveal technique inefficiencies. Concept2 emphasizes this in their guidance:

"Maximum speed only happens when the best technique is matched to a sustainable spm".

If your stroke rate increases but your split times don’t improve, it’s often a sign of a power or technique breakdown. Advanced metrics like Stroke Efficiency and Check Factor can help refine power distribution. Elite rowers, for example, typically achieve Stroke Efficiencies between 2.5 and 3.5, with catch durations under 0.35 seconds. Even a small improvement – like a 1% gain in drag efficiency – can shave off about 1.4 seconds in a 2,000m race.

By leveraging these metrics, rowers and coaches can combine data sources to further sharpen training strategies.

Combining GPS and Impeller Data

While stroke rate analysis offers valuable insights, combining it with data from GPS and impeller systems paints a more complete picture of rowing performance. For training sessions on rivers, impeller data measures effort by tracking speed through the water, while GPS data focuses on navigation and overall speed over ground. Together, these tools provide complementary feedback, with impeller data offering immediate insights and GPS data helping with broader performance assessments.

Breaking down the data into five-stroke blocks allows for a detailed evaluation of technical adjustments, such as refining catch timing. When combined with metrics like stroke count, relative boat speed, and heart rate-based training load, this approach explains up to 50% of session intensity variance. This multi-faceted analysis gives coaches a clearer understanding of training demands than stroke rate data alone, leading to more precise and effective training plans.

Conclusion

GPS and impeller systems approach the measurement of stroke rate and speed in distinct ways. Impeller systems focus on water-relative speed, capturing the actual flow past the boat with an accuracy of under 2%, even in changing currents. On the other hand, GPS systems measure ground-relative speed, offering reliable results on still water but becoming less accurate when currents are present. These differences highlight the trade-offs between the two methods.

Impeller systems, while requiring initial setup for optimal performance, provide consistent, stroke-by-stroke feedback. GPS systems, in contrast, are simple to use straight out of the box, making them a convenient option for rowers who frequently switch boats. However, standard GPS units can have velocity errors exceeding 10% on a single stroke, though newer 5 Hz receivers have improved responsiveness.

For rowers, the choice between these systems often depends on the water conditions they train in. On rivers or tidal waters, impeller data ensures that split times reflect actual effort through the water, unaffected by current. Meanwhile, GPS works well on still water, offering reliable data on distance and average pace. For the best of both worlds, a dual-mode device that switches between GPS and impeller modes can provide comprehensive feedback, ensuring accurate stroke rate measurement and enhancing both training and racing performance.

FAQs

How do impeller systems stay accurate in moving water?

Impeller systems measure a boat’s speed by tracking its movement relative to the water, not the land. This approach avoids inaccuracies caused by currents or tides, offering a more dependable measure of actual speed compared to GPS, which calculates speed based on land movement.

By concentrating on how water flows around the boat, these systems deliver steady and precise speed readings, making them particularly effective in conditions where water movement could otherwise skew the data.

Why are GPS systems less accurate for measuring individual strokes?

GPS systems calculate boat speed based on its movement relative to land. However, this measurement can be affected by external factors like water currents, making it less accurate for determining the speed of individual strokes. Since GPS averages speed over a larger distance, it doesn’t capture the nuances of each stroke. For more accurate, stroke-by-stroke data, many rely on impeller-based systems. These devices measure speed relative to the water itself, offering a clearer picture of performance without land-based influences.

What are the advantages of using a hybrid GPS and impeller system for rowing?

Using a hybrid GPS and impeller system gives rowers and coaches a better way to track performance with greater precision. GPS measures speed relative to land, while impellers focus on speed relative to water. This dual approach helps factor in environmental elements like wind and currents, offering a clearer picture of rowing efficiency.

Each technology has its own limitations, but combining them bridges the gaps. GPS data updates less frequently, which can make it harder to analyze performance stroke by stroke. On the other hand, impellers provide immediate feedback. Together, they deliver real-time, accurate data that helps rowers fine-tune their technique, enhance training sessions, and sharpen race strategies. These systems have become essential for those aiming to perform at their best.